CPS approach to training & health

Given that training is a complex problem, it cannot be approached with recipe manuals. However, this doesn’t mean it should be random or that it's best to proceed without a plan.

The reductionist view of training studies problems in isolation. The coach focuses on training, the physiotherapist on injuries, and the nutritionist on food. No one takes the time to understand the athlete's habits and routines, their motivations, what they want to achieve, what values they hold, and how all these variables influence each other and change as they interact with one another and with the daily and diverse events they face.

As a result, we have a plethora of metrics that seem extremely useful for coaches but are of no value to the athlete—or, at best, make their training worse. The ability to measure things like time in zone or TSS gives us a false sense of control over the athlete's performance, which soothes us and gives us that sense of security we need, even though it's false. This is what I call the “tunnel vision” of performance: too much focus on what we can control and ignorance of what we cannot.

The drive to improve results—and not the system as a whole, which is generally not even understood—ends up creating interventions aimed at improving metrics that show short-term gains at the cost of long-term harm or maladaptation. When a metric becomes a goal, it ceases to be a good metric. We have mistaken time in zone or TSS as a way to measure training with the belief that adaptation depends on accumulating more of these markers. We have confused the power meter as a good tool to measure physiological responses with the idea that physiological responses depend on watts.

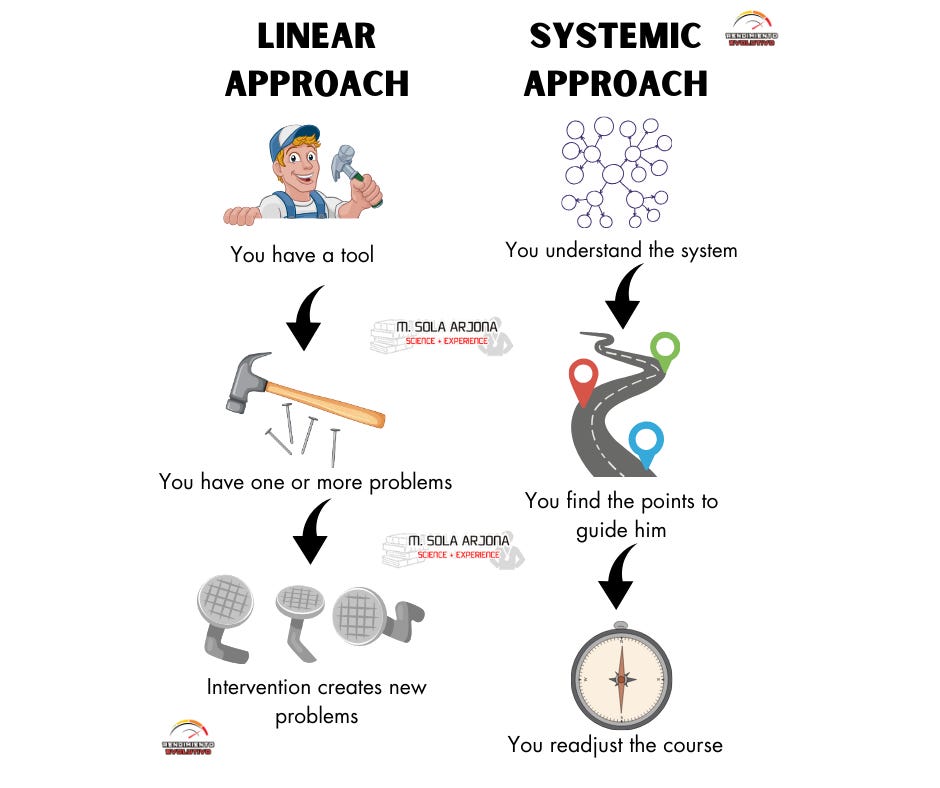

The traditional coach uses the linear theory of training to try to improve the markers that indicate the state of the body, but they have no idea how the body works. They have a tool: the power meter; and they use it to try to solve everything by measuring training loads, hours, and sets. When they act, they seem to succeed. But it’s like trying to lose weight long-term by only going on a diet: an intervention destined to fail, with a yo-yo effect that will generate even more problems in the future.

The systemic approach to training is much more humble. It understands that there are no recipes and that to address the training process, the first thing is to learn a lot—an immense amount—about how the body works. Understanding how the parts function, traditional physiology, and how they interact: complex systems. Knowing a lot about psychology, nutrition, or healthy lifestyle habits. Knowing about the athlete: their goals, values, relationships, socio-economic context, training history, etc.

With all this knowledge, we can then analyze which points we can use to guide—not dominate—the athlete towards a better path. What error points do we detect? What habits can we change? How can we do it so that they integrate it into their routines? How can we keep them motivated?

We intervene, analyze our intervention, and adjust the course. Is the athlete improving by applying this new stimulus? Is it an improvement that can be sustained? Are they enjoying it? Could it be done better? This is the most important point: trial and error. To master it, we need to maintain control over the changes applied. If we change the stimuli we give each week or alter several training sessions and aspects of our lives at the same time, we won’t be able to know what is working or why.

We need to allow enough time to see what effect the changes have on the athlete. It’s like trying to find a destination in a mountain range without a map: if we never adjust our course, we will end up lost, but if we change it all the time, we will end up the same, wandering in circles.

We need to be able to detect when an intervention or training session stops giving us benefits and when we need to change course, but at the same time, we must allow enough time to determine if we need to change course or if we are heading in the right direction.

It’s about “dancing” with the system to adjust to the needs of each moment. Since we are never in the same situation—nor are we the same person—the training program must be flexible and proactively adjust to changes in the environment. If a week of heavy work comes up, we adjust by training more lightly.

To do this, obviously, the training process must be co-designed between athlete and coach. The coach has something the athlete doesn’t know: the theoretical knowledge of how the body works and the practical experience to know how to act in different circumstances. But the athlete has something the coach needs to be able to work: their perceptions and sensations.

Only the athlete knows their level of fatigue and mood, their perception of effort or pain, their desires and values, or the social changes they experience daily. Without these, it is impossible for the training program to be appropriate: it will simply be another recipe that works in the short term, thanks to the athlete's body compensating for the problems generated. But ineffective and harmful in the long run.

The coach doesn’t have to “push” or “force” the athlete to follow the plan. If the athlete feels this way, they will usually fail. An appropriate training program feels easy: the load decreases if you feel tired, and it increases when you feel like training. Coach and athlete row in the same direction, without placing the program above the preferences.

If you liked this article, you will like my book: “The Nature of Training, Complexity Science Applied to Endurance Performance”.

I'm currently reading your excellent book. I came to sports coaching from an organisational leadership and non-directional executive coaching background, where chaos and complexity theories plus other models to understand the individual and organisations in different ways from relatively static and 'one-dimensional' views, are available. This article is a superb and succinct reminder of the 'big picture' of performance development for coaches and athletes. The schedule is the servant of the person. The mind is not stronger than the body. You do not need pain to have gain. Thankyou for sharing your practice and ideas.

Great article!