Durability: Is there any Fourth Dimension?

How can the same cyclist win both a 20-minute stage and a 6-hour stage?

What I want to highlight in this article is that durability, like performance, is not fragmented into different parts and that what is understood by "durability" is nothing more than a compensation by the physiological network in response to fatigue accumulation; this affects how physiological synergy is configured (whether the percentage of VO2max, efficiency, perceived exertion, thermoregulation, etc., increases or decreases)...

The things that improve durability are the same things that improve endurance, because durability is an expression of endurance. And this is why, simply, athletes with better aerobic capacity, better ability to tolerate RPE, better thermoregulation capacity, etc., have greater durability. And this has been clearly shown in how the results of a 20-minute stage and a 6-hour stage are similar.

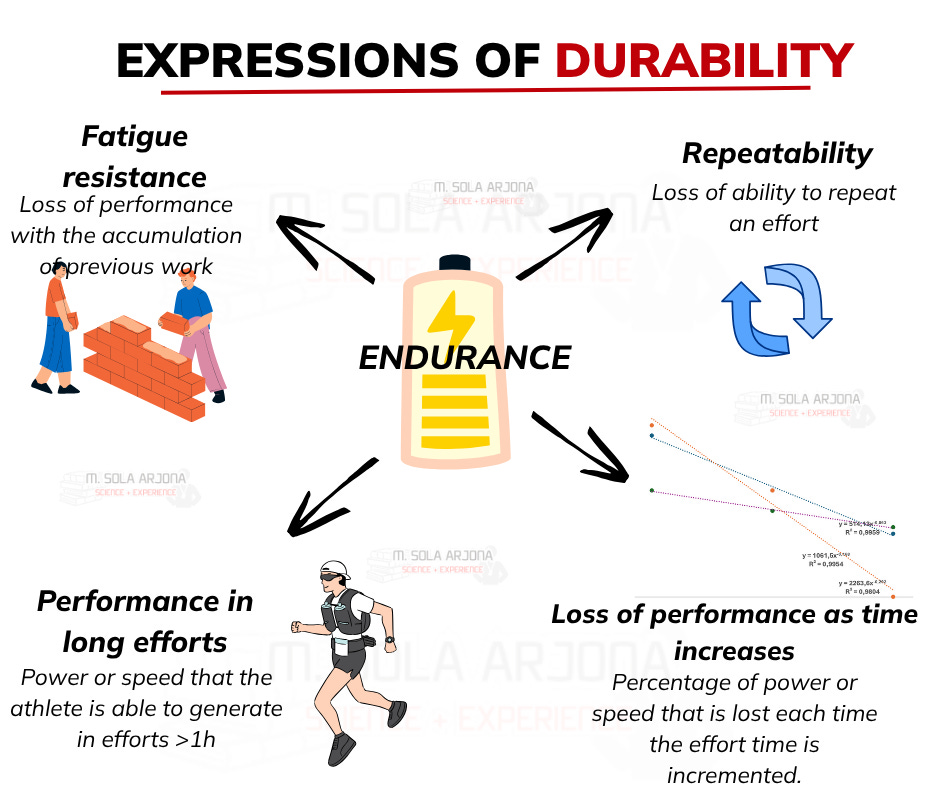

Durability is defined as “time of onset and magnitude of deterioration in physiological-profiling characteristics during prolonged exercise”.

Some authors argue that durability is the 4th physiological dimension of endurance exercise, adding to oxygen uptake, efficiency, and anaerobic capacity, since no clear relationship has been found between durability and one or more of the other three dimensions.

I am quite critical of this idea, as it seems to me to continue along an erroneous path and model of understanding the human body, one that separates it into independent and unrelated parts or factors. And because this model is flawed, contradictory results emerge, which we navigate by saying that there are “new dimensions that appear and we don’t know why.”

If we were to say that durability is the 4th dimension of performance, then we would have to talk about a 5th dimension: capacity to cope with effort perception.

And of course, a 6th dimension, that could be thermoregulation capacity. Even if it is unrelated to the previous five, it is undoubtedly vital for sustaining power over time and will be decisive in durability and efforts in the heat.

And why not a 7th dimension that affects performance, specially in running, like muscle capacity to contract, endure microdamages and generate power?

Or an 8th dimension, the ability to absorb nutrients during exercise?.And so on, ad infinitum.

In short, it looks like a mistake to compartmentalize physical qualities in this way, as if they were sums: “aerobic + anaerobic + efficiency + durability + motivation + strenght + fatige = watts.” In reality, these are circular causal relationships, where a change in any parameter affects the others.

For me, the concept of durability is just another one of those ideas that would never have existed without first inventing laboratory tests—a theory that no athlete truly feels as such in real sport. Like so many others.

Don’t get me wrong. Of course performance declines with the onset of fatigue, but how this affects VO₂max or efficiency is not what we’re looking for, because all these factors already influence each other.

Durability is nothing more than a concept born from our desire to simplify endurance. And the factors that influence each expression of endurance are the same: aerobic capacity, motivation, thermoregulation capacity, nutrition, posture, pain tolerance, etc.

All functional expressions of durability stem from the same thing: improving endurance.

And we have seen this yet again in the time trial of this Tour de France.

Although we are bombarded with the idea of training durability specifically—doing intervals at the end of sessions, focusing on the first lactate threshold, etc.—once again we see that the time trial ranking is almost identical to that of the long mountain stages, with slight modifications due to the natural day-to-day performance fluctuations of the athletes.

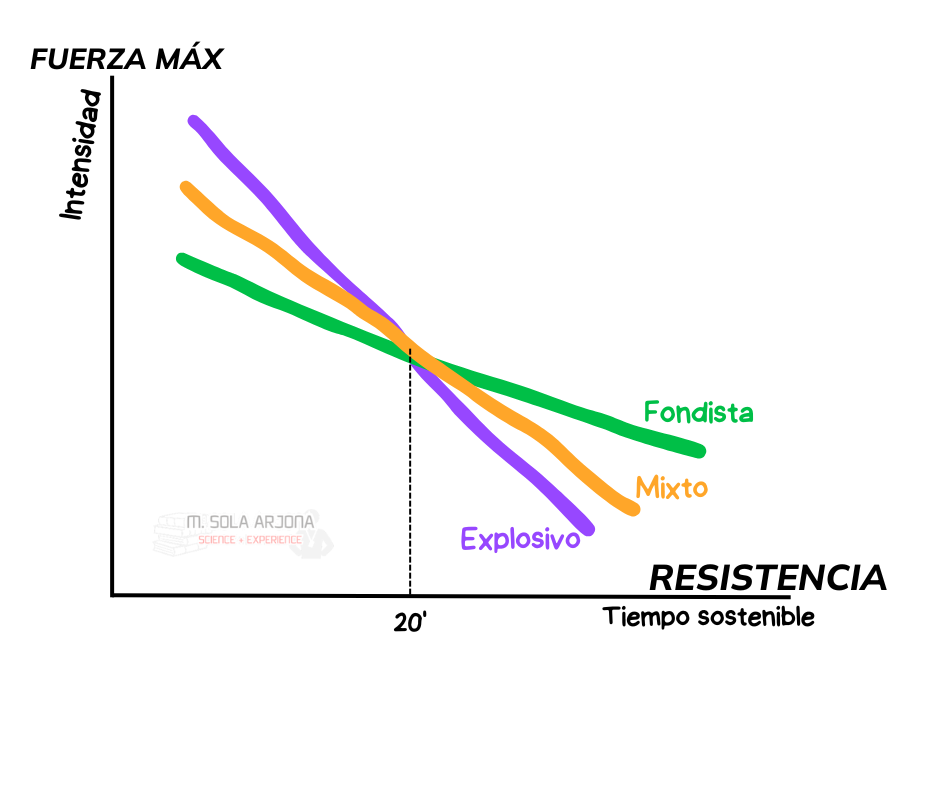

If durability were a separate ability, a different stress that must be trained differently from aerobic capacity, we would expect to see specialists in this type of effort and others who are much better after 5 hours of riding. But what we always see is that the rider who is better at 20-minute efforts is also better at 60-minute and 300-minute efforts.

In other words, the athlete with good aerobic condition and good efficiency dominates, and the longer the race, the greater their advantage. In real world, the very fit endurance athlete is working at a slower relative percentage of intensity that the less fit; and with the accumulation of time, the difference between them grows.

This reinforces what we have observed when analyzing power-duration relationships in many athletes: they follow a power-law.

The exponent of this power-law differs between athletes—some lose a higher percentage of power when exercise duration doubles—but this exponent keeps similar across all durations. That is: if you are more resistant than another person, you are expected to outperform them in a 1-hour effort compared to 15 minutes; but it is even more likely you will outperform them if the effort lasts 4 hours. With better endurance, the longer the exercise, the better your relative performance; and vice versa.

That is why today we saw Pogacar, who after shining in stages where he accumulated more than 2h30’ at 6 W/kg and 3000 kJ (such as this one I analyzed here), also crushed a climb of just over 20 minutes, pedaling at over 7.3 W/kg, achieving the best performance of this duration in history.

**Rereading the article, I think I’m missing a lot of context to rigorously explain what I want to explain. I find this idea of the concept of "durability" as if it were revolutionary extremely frustrating — that in the 21st century there are studies (funded with public money) saying, "hey, accumulated fatigue matters," but "we don’t know how or why, so we’ll call it a 4th dimension we’ve just discovered." Damn, seriously? Is the best we can do really to say that we’ve discovered that fatigue affects athletes’ performance, but we don’t know how or why or how best to train it? And yet one paper after another reinforces an idea that just doesn’t hold up…

I think we should carefully rethink what we mean by and how we measure this concept called durability.

The studies to date have shown that no specific type of training has been found to improve durability better than others, nor a clear relationship with any other factor—apart from the athlete’s aerobic capacity.

This tells us that the organism is extremely complex, with all its functions and systems interwoven, and that we need a new paradigm to understand it: the Complex Systems Paradigm.

In my next book I will delve much deeper into these ideas; until then, you can read the first one.

An interesting conversation that gives context to the post :)

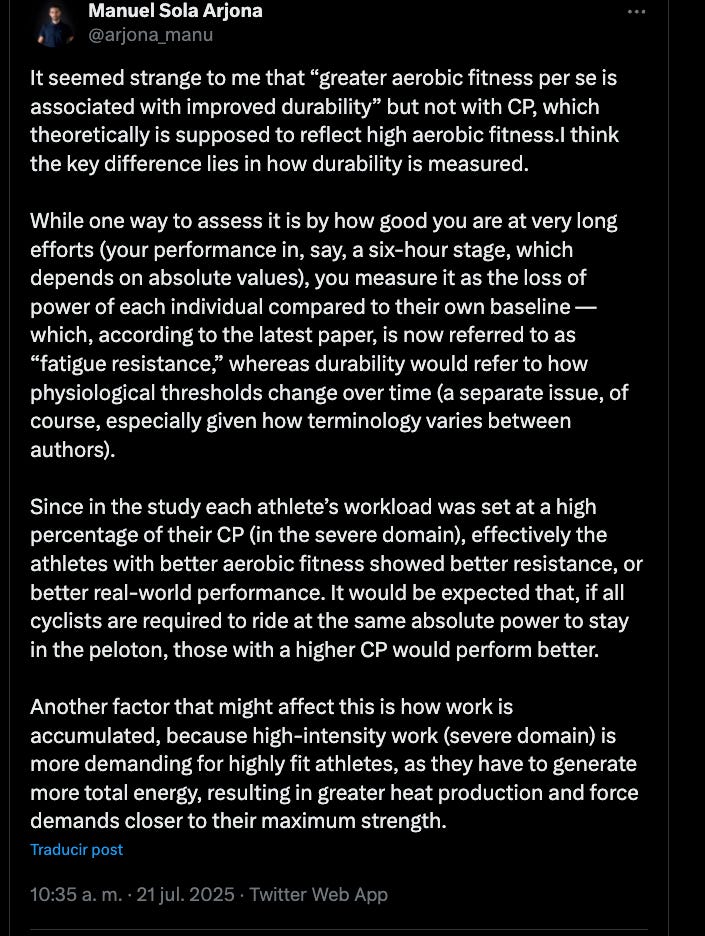

It seemed strange to me that “greater aerobic fitness per se is associated with improved durability” but not with CP, which theoretically is supposed to reflect high aerobic fitness.I think the key difference lies in how durability is measured.

While one way to assess it is by how good you are at very long efforts (your performance in, say, a six-hour stage, which depends on absolute values), you measure it as the loss of power of each individual compared to their own baseline — which, according to the latest paper, is now referred to as “fatigue resistance,” whereas durability would refer to how physiological thresholds change over time (a separate issue, of course, especially given how terminology varies between authors).

Since in the study each athlete’s workload was set at a high percentage of their CP (in the severe domain), effectively the athletes with better aerobic fitness showed better resistance, or better real-world performance.

It would be expected that, if all cyclists are required to ride at the same absolute power to stay in the peloton, those with a higher CP would perform better. Another factor that might affect this is how work is accumulated, because high-intensity work (severe domain) is more demanding for highly fit athletes, as they have to generate more total energy, resulting in greater heat production and force demands closer to their maximum strength.

Excelente, me gustó muchísimo eso de las otras dimensiones, que podría hacer un cuerpo si no puede alimentarse o sin la parte cognitiva/mental/motivacional. Sin duda una excelente percepción de lo que verdaderamente debe ser la comprensión de este y otros deportes de resistencia.👌💯

This argument has merit for cyclists ( I am no expert on cycling ) but in running it falls down - 10km runners don’t win marathons and marathon runners don’t win ultras . Training is different - and those that excel in a 10km need to change their training to excel in a marathon .